Willem Adriaan ‘Wim/Jimmy’ Giel (1909 - 1976)

Personal Background

With his parents, 1909 - 1910

With his parents, 1909 - 1910

Willem Adriaan Giel was born on 15th May 1909, at his parents' home in Magelang, Central Java, Dutch East Indies. He was born of Adriana Louise Clignett and Willem Hendrik Frederik Giel, also known as 'Henri'. Both were Dutch but born in Java, Henri in Surabaya in 1884 and Adriana in Batavia (now Jakarta) in 1885. They were married in The Hague in September 1907.

Henri was a test pilot based at Kalidjati (or Kalijati, now Suryadarma) Airbase in Kalidjati, close to Bandoeng. He had been trained at KNIL Cadet School, followed by Royal Military Academy, after which he was appointed 2nd lieutenant of Infantry in the Army in the Dutch East Indies and involved in active service. In 1920 he got his pilot's licence and soon was in charge of testing new aircraft. Tragically on 25th January 1923, a test flight proved fatal: when Henri tried to land at the airbase, the Viking amphibious aircraft he was flying did not respond properly, clipped some trees and crashed. Willem Adriaan was only thirteen at the time.

After his father's death, Willem Adriaan (who was also known as ‘Wim’ or ‘Jim/Jimmy’) attended High School in Nijmegen for three years. He then attended the Maritime Academy in Den Berg, Texel. In 1933, Wim passed his diploma to become 3rd Officer (Mate) of Merchant Marine Ships, working for KPM (Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij). He worked his way up the ranks and by 1939 he was 1st Officer, with the right to act as Captain on a seafaring vessel of the Merchant Navy. Almost a year after the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, in April 1941, he crossed the sea in a boat to England as an 'Engelandvaarder'. This has become an accepted term for those that crossed the North Sea to England from the Netherlands by boat; however, the literal translation means England paddlers or sailors.

Henri was a test pilot based at Kalidjati (or Kalijati, now Suryadarma) Airbase in Kalidjati, close to Bandoeng. He had been trained at KNIL Cadet School, followed by Royal Military Academy, after which he was appointed 2nd lieutenant of Infantry in the Army in the Dutch East Indies and involved in active service. In 1920 he got his pilot's licence and soon was in charge of testing new aircraft. Tragically on 25th January 1923, a test flight proved fatal: when Henri tried to land at the airbase, the Viking amphibious aircraft he was flying did not respond properly, clipped some trees and crashed. Willem Adriaan was only thirteen at the time.

After his father's death, Willem Adriaan (who was also known as ‘Wim’ or ‘Jim/Jimmy’) attended High School in Nijmegen for three years. He then attended the Maritime Academy in Den Berg, Texel. In 1933, Wim passed his diploma to become 3rd Officer (Mate) of Merchant Marine Ships, working for KPM (Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij). He worked his way up the ranks and by 1939 he was 1st Officer, with the right to act as Captain on a seafaring vessel of the Merchant Navy. Almost a year after the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, in April 1941, he crossed the sea in a boat to England as an 'Engelandvaarder'. This has become an accepted term for those that crossed the North Sea to England from the Netherlands by boat; however, the literal translation means England paddlers or sailors.

Historical Context

The Nazis had invaded the Netherlands on the 10th May 1940 and the first months under military rule were quite bearable. Nearly a year later however, the Dutch were all on ration stamps. Famine had not yet reached them but a shortage of food was expected with the coming winter. Meat was very scarce (500g every 10 days) and often not available. People were allocated points to buy clothing (100 points every 6 months – a suit was 80 points and a shirt 30).

As soon as the Nazis had invaded the Netherlands, the Austrian Nazi politician Seyss-Inquart (derisively known as ‘Zes en een kwart’ by the Dutch, a play on his name meaning ‘six and a quart’) was appointed Reich Commissioner (Reichskommissar) by Hitler. He encouraged the fascist Dutch NSB (Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging – National Socialist Movement), the only political party allowed in the Netherlands by the end of 1941. The NSB formed a paramilitary Home Guard (Landwacht), which acted as a civil authority, and its members were slowly and surely appointed to high positions such as generals, mayors and provincial commissioners. There was terror in the streets, an unusual sight in Holland. All shop windows were boarded at night. Radical stipulations to the Dutch people’s civil rights and persecution of the Jews followed, resulting in a general strike in Amsterdam, often known as 'The Strike of February 1941'.

Dutch resistance movements were greatly stimulated by the strike and made significant actions by way of pamphlets, sabotage and so on. The Germans were largely ignored. The BBC and Radio Oranje were generally well listened to with the risk of 9 to 12 months imprisonment, in addition to a huge fine, if caught. All the street urchins whistled popular songs from the illicit radio stations the next day. Money was replaced with Guilder (Hfl. 1.--) and Rijksdaalder (Hfl. 2.50) coupons.

As soon as the Nazis had invaded the Netherlands, the Austrian Nazi politician Seyss-Inquart (derisively known as ‘Zes en een kwart’ by the Dutch, a play on his name meaning ‘six and a quart’) was appointed Reich Commissioner (Reichskommissar) by Hitler. He encouraged the fascist Dutch NSB (Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging – National Socialist Movement), the only political party allowed in the Netherlands by the end of 1941. The NSB formed a paramilitary Home Guard (Landwacht), which acted as a civil authority, and its members were slowly and surely appointed to high positions such as generals, mayors and provincial commissioners. There was terror in the streets, an unusual sight in Holland. All shop windows were boarded at night. Radical stipulations to the Dutch people’s civil rights and persecution of the Jews followed, resulting in a general strike in Amsterdam, often known as 'The Strike of February 1941'.

Dutch resistance movements were greatly stimulated by the strike and made significant actions by way of pamphlets, sabotage and so on. The Germans were largely ignored. The BBC and Radio Oranje were generally well listened to with the risk of 9 to 12 months imprisonment, in addition to a huge fine, if caught. All the street urchins whistled popular songs from the illicit radio stations the next day. Money was replaced with Guilder (Hfl. 1.--) and Rijksdaalder (Hfl. 2.50) coupons.

Escape from the Nazi occupied Netherlands

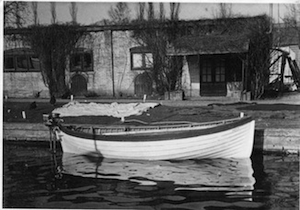

In the dark of evening on the 4th April 1941, six cold Dutch men in a lifeboat called ‘Keesje’ landed near Lowestoft on the English coast. A bunch of orange tulips had also made the journey from the Netherlands. Blowing a foghorn to sound their arrival, they were soon greeted with cries of ‘hands up’ by the British military. They were ‘Engelandvaarders’ who had made the difficult journey across the North Sea by boat to escape the Nazi occupied Netherlands. They were fortunate to make the crossing where others had failed, but their thorough preparation, suitable qualifications and help by good people had given them the best chance of success.

The men were lr. JMD. de Niet, lr. JE. Woltjer (both qualified engineers, indicated by the Dutch title 'lr'), E. Klein (a dealer of electrical appliances), Hendrik Willem Keesom, Willem Adriaan ‘Jimmy’ Giel (my Opa) and Lourens Van der Veen (three naval officers). Each man had his own reasons for escaping. The situation was probably enough but Opa had also recently found out that he was on the German blacklist*, so one more reason to leave Holland. [*a family member told me that Opa had been on shore leave in Amsterdam, taking a walk with a Jewish friend called Rudi Hans. Rudi was shot by a German officer and Opa had to run for his life. It has not been possible to confirm this event].

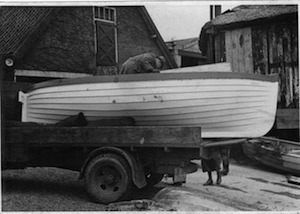

In March 1941, Keesom, a naval colleague of Opa, told him of a plan to escape to England in a boat. The same afternoon Opa met with De Niet, one of the initiators of the plan, and also Van der Veen and Keesom to discuss plans and charts. A few days later Woltjer joined them. Finance was agreed and their plans were finalised – within a week a lifeboat was purchased in Slikkerveer near Rotterdam and an outboard motor in Amsterdam.

The boat was loaded onto a truck and driven to Leiden, where the motor was also picked up, and taken to market gardener/vegetable grower C. Hogewoning in Katwijk aan de Rijn. The motor and boat were fixed together and tested in Warmond, on De Kaag. Hogewoning’s 16- year old student son Kees was the namesake for the boat, the ‘Keesje’. Kees asked Piet Ravenbergen if his barge the ‘Henry’ could be used to transport the boat to Hellevoetsluis.

The men were lr. JMD. de Niet, lr. JE. Woltjer (both qualified engineers, indicated by the Dutch title 'lr'), E. Klein (a dealer of electrical appliances), Hendrik Willem Keesom, Willem Adriaan ‘Jimmy’ Giel (my Opa) and Lourens Van der Veen (three naval officers). Each man had his own reasons for escaping. The situation was probably enough but Opa had also recently found out that he was on the German blacklist*, so one more reason to leave Holland. [*a family member told me that Opa had been on shore leave in Amsterdam, taking a walk with a Jewish friend called Rudi Hans. Rudi was shot by a German officer and Opa had to run for his life. It has not been possible to confirm this event].

In March 1941, Keesom, a naval colleague of Opa, told him of a plan to escape to England in a boat. The same afternoon Opa met with De Niet, one of the initiators of the plan, and also Van der Veen and Keesom to discuss plans and charts. A few days later Woltjer joined them. Finance was agreed and their plans were finalised – within a week a lifeboat was purchased in Slikkerveer near Rotterdam and an outboard motor in Amsterdam.

The boat was loaded onto a truck and driven to Leiden, where the motor was also picked up, and taken to market gardener/vegetable grower C. Hogewoning in Katwijk aan de Rijn. The motor and boat were fixed together and tested in Warmond, on De Kaag. Hogewoning’s 16- year old student son Kees was the namesake for the boat, the ‘Keesje’. Kees asked Piet Ravenbergen if his barge the ‘Henry’ could be used to transport the boat to Hellevoetsluis.

On the 19th March, Keesom and Opa sailed the boat to another place where they met up with the others and they and the ‘Keesje’ were stowed onto the barge. The boat was stored under bales of straw in the hold. Piet Ravensbergen and his son Gerrit took the barge and its illicit cargo along canals to Delft, Rotterdam and then Simonshaven. The barge was moored in the harbour of the pumping station De Biersum, Biert, near to Hellevoetsluis. The operator of the pumping station, Maarten de Graaff (a former navy man and member of the Dutch resistance), was in on the plot and his house was used as a gathering place for the Engelandvaarders.

They unloaded the boat from the barge and tested the outboard motor, which unfortunately did not work. Everyone was disappointed. They stayed the night on the barge and the next day stored the boat and went home separately. They reconvened feeling more energised several days later, exchanged the outboard with the help of motorcycle importer H. Joosten from Amsterdam and prepared everything for assembly. The Engelandvaarders were hidden in the pumping station.

They unloaded the boat from the barge and tested the outboard motor, which unfortunately did not work. Everyone was disappointed. They stayed the night on the barge and the next day stored the boat and went home separately. They reconvened feeling more energised several days later, exchanged the outboard with the help of motorcycle importer H. Joosten from Amsterdam and prepared everything for assembly. The Engelandvaarders were hidden in the pumping station.

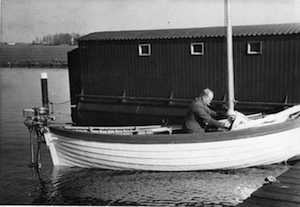

lr. de Niet and two shipbuilders met at Hellevoetsluis on the 2nd April and the outboard motor was installed. However, it was discovered that the propeller shaft was too short. Very early on the morning of the 3rd, De Niet rode to Rotterdam on his bicycle, managed to get a new propeller shaft and was back by 16:00, a 60km round trip. He then took the shipbuilders home (another 20km!) and they were all ready to leave at 22:00. Hogewoning, the father of Kees, had provided them with some orange tulips from Katwijk to take to give Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands who was exiled in London.

They left via the Haringvliet. While they were waiting for the tide, they heard a truck coming. The Engelandvaarders thought it was other people who were going to board the boat and travel with them, but moments later saw the helmets of soldiers. They quickly cast off the boat and drifted on the tide in the darkness. The Germans arrested some people who were still ashore. It is not known what happened to them afterwards.

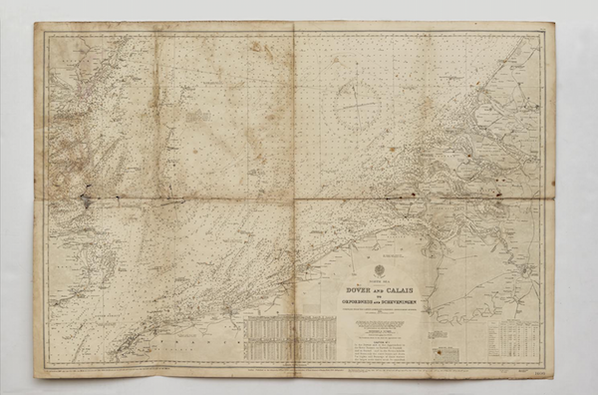

Opa had charted all the routes and distances and took charge of the rudder and compass. After 3⁄4 hour they became stranded, but luckily only once. They reached the open sea at 00:30. About a foot of water had flooded the boat and the engine failed. They decided to sail in the swell and De Niet was seasick. After about an hour they managed to restart the engine. There was continuous spray into the boat so they put a spray protector up. They could see the English coastline in the daylight but with the wind and sea getting stronger, they needed to get to shore before dark.

They left via the Haringvliet. While they were waiting for the tide, they heard a truck coming. The Engelandvaarders thought it was other people who were going to board the boat and travel with them, but moments later saw the helmets of soldiers. They quickly cast off the boat and drifted on the tide in the darkness. The Germans arrested some people who were still ashore. It is not known what happened to them afterwards.

Opa had charted all the routes and distances and took charge of the rudder and compass. After 3⁄4 hour they became stranded, but luckily only once. They reached the open sea at 00:30. About a foot of water had flooded the boat and the engine failed. They decided to sail in the swell and De Niet was seasick. After about an hour they managed to restart the engine. There was continuous spray into the boat so they put a spray protector up. They could see the English coastline in the daylight but with the wind and sea getting stronger, they needed to get to shore before dark.

Copies of the maps Opa used to chart the crossing. Top - Haringvliet, bottom - North Sea. Both signed on the back by him ‘This is the map I used, when I escaped from Holland during the 2nd World War, on 2nd April 1941’ (written retrospectively, but I believe must be the date he charted the routes). Both maps have markings on them, I assume to show the course they took.

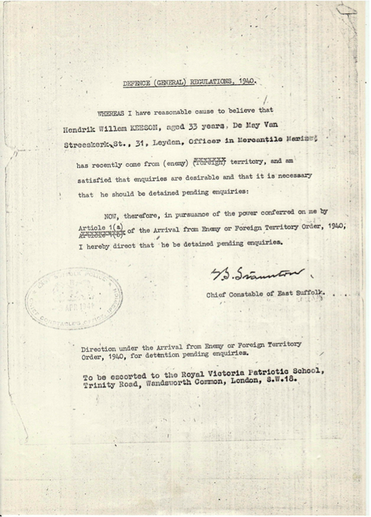

At 18:30 they hailed an English freighter and were told the course and directions for Lowestoft. Unfortunately the engine broke down again and because they had such cold hands could not get it working again for another hour. It was now dark and there was no sign of Lowestoft. They decided to get as close as possible to shore, switched on their light and blew on the foghorn. A boat pulled up a short while afterwards and they were told to put their ‘hands up’. After some minutes everything was ok and they were taken to some barracks where the English were very hospitable. Later they were taken to the Chief Constable’s Office of East Suffolk Police in Ipswich and got to bed at 04:30 on the 5th April. The next day they were escorted to an internment camp in London at the Royal Victoria Patriotic School, Trinity Road, Wansworth Common, London SW18.

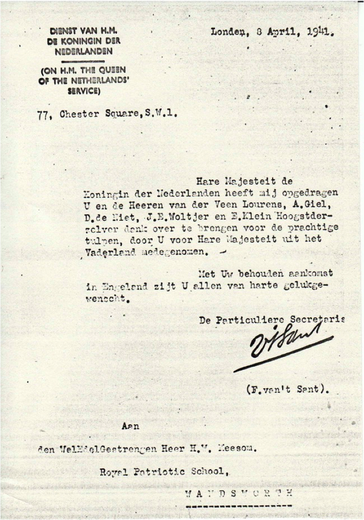

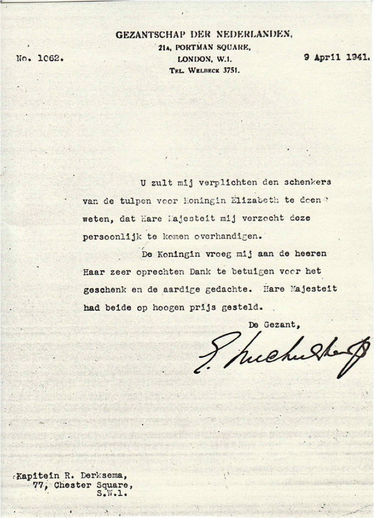

Queen Wilhelmina received the tulips (most likely now wilted) and on the 8th April 1941 the Engelandvaarders received a letter from her private secretary F. van’t Sant saying that the Queen wished to pass on ‘her sincere thanks for the beautiful tulips’. A bunch was also passed onto Queen Elizabeth (The Queen Mother), who also conveyed her thanks for the gift on 9th April via the Dutch envoy.

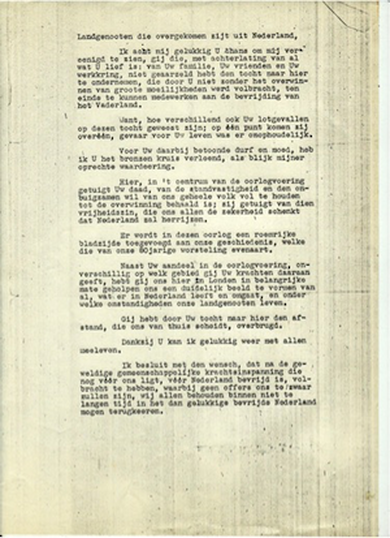

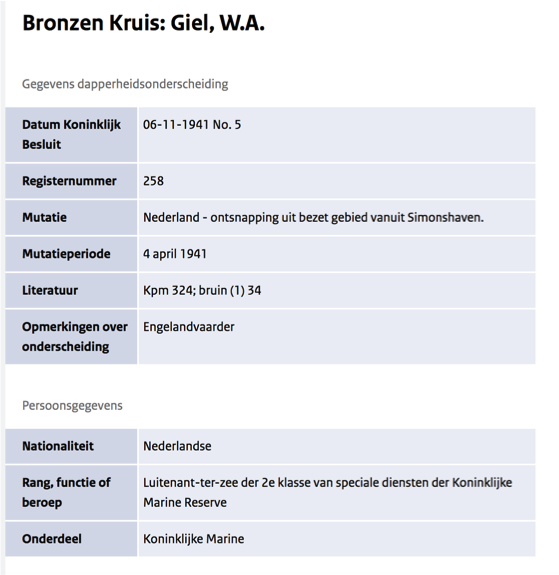

The men were invited to the London wartime residence of Queen Wilhelmina and Prince Bernhard to report to them about the situation in the Nazi occupied Netherlands. One evening, shortly after their crossing, the message "Keesje has arrived" was heard on Radio Oranje. On the 2nd June 1941 (Whit Monday), Kees Hogewoning heard a broadcast from London on the radio. The announcer said ‘I have got the following message for you: the tulips have arrived safely and they are fine’. All the crew received a Bronze Cross (Bronzen Kruis) medal on the 6th November 1941 for their part in the journey. The Bronze Cross was awarded for skill or bravery in the face of the enemy and was introduced by royal decree by Queen Wilhelmina on 11th June 1940 in London. Opa also received a commemorative model of the boat, but unfortunately that was subsequently ruined when my Uncle Brian chewed it!

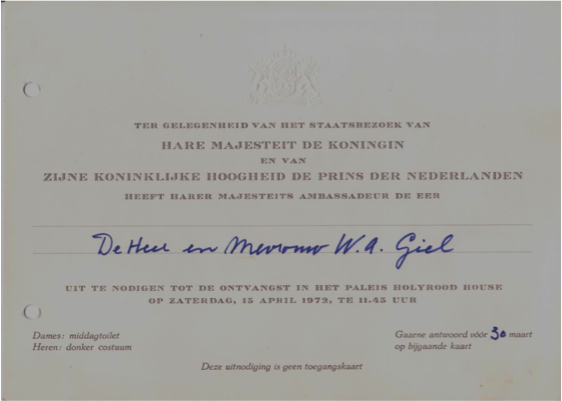

Opa subsequently moved to Scotland where he continued his naval career, first in the exiled Dutch Royal Navy in Dundee and then as a merchant sea captain. Thirty-one years later, my Oma and he met Queen Juliana and Prince Bernard at Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh on the 15th April 1972.

Marten de Graaff, was posthumously awarded the Resistance Cross in 1971. He bravely risked his life to save this group of Engelandvaarders and many others like them. Sadly he was betrayed the following year by another so-called resistance fighter and his life was ended in a concentration camp. I find his arrest and demise particularly poignant. My Opa managed to make his journey to England without being caught by the Nazis, despite how many people were in on the plot. This group of Engelandvaarders may have been well equipped for a sea crossing, but they were also extremely lucky to have such a trustworthy and dependable group of helpers. Otherwise, the story might have ended quite differently and I for one would not be here!

Epilogue

A plaque (no. 9152) now resides on 23 Hyde Park Place, London W2, to commemorate the building having served as a club, the Oranjehaven, bestowed in 1942 by Queen Wilhelmina for Dutchmen who had escaped their occupied country to join the Allied Forces.

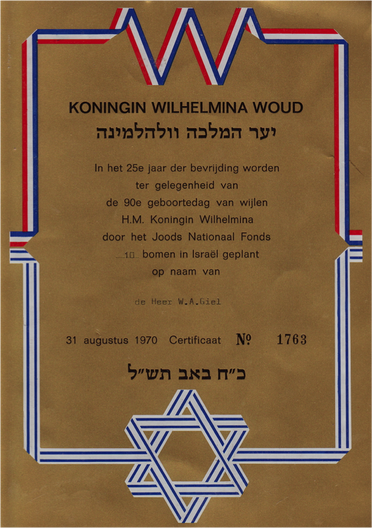

On August 31st 1970, 25 years after liberation and to mark the 90th birthday of the late Queen Wilhelmina, the ‘Joods Nationaal Fonds’ (Jewish National Fund) planted some trees in ‘Queen Wilhelmina Forest’ in Israel in Opa’s name (certificate no. 1763). I would like to think he was given this, but it may well be that he bought the plot.

Ir. JMD. de Niet later became director of the Rotterdam shipyard Wilton Fijenoord and Ir. JE. Woltjer director of the Holland America Line. During the Second World War, Wilton Fijenoord shipyard built submarines for the Germans and grew its workforce while other shipyards dwindled. The management were imprisoned after the war for their collaboration. The barge the ‘Henry’ survived the war, through shelling by German and British aircraft. It was sold immediately after the war to a Rijnsburgse bear skipper. The barge, now called ‘Anno 2013’, is still in the service of an Amsterdam water policeman.

Marten de Graaff

Maarten de Graaff, a focal kingpin in this tale, had his own very interesting, if not tragic, story. He helped many Engelandvaarders escape the Netherlands during the Second World War but in the end was betrayed and his life was ended in a concentration camp.

Born in Rozenburg on the 8th December 1874, he lived on his father’s farm for nineteen years. In 1915, he moved with his wife to Simonshaven, where he worked as the operator of the pumping station and also ran the ferry service from Piershil on the Spui to the Biersum on Putten. There used to be small port with a jetty at Piershil. Pedestrians and cyclists could pull on a bell and the ferryman would take them in his rowboat to the Biersum on Putten (Putten translates as Wells).

When the Nazis invaded the Netherlands, Maarten de Graaff joined the resistance. He was 65 years old. He was part of a team who helped prepare crossings to England for Engelandvaarders. One of the ways in which he did this was by taking ‘passengers’ offshore in the dark in his speedboat where they were picked up by a British submarine. He would then wait until the tide turned and quietly return to shore in his boat.

On the 21st March 1942, another so-called resistance fighter Henk Luyendijk, a driver from Rotterdam, betrayed him. In December 1941 a plan was put together to take a number of people, mostly Jews but also some marines, to England. Henk was in on the plan from the beginning, which he revealed to the Gestapo. He also delivered petrol needed for crossings to the resistance. The quality of petrol was tested regularly and one day his ‘petrol’, whilst it smelt of petrol, was clearly not. When he was told, he felt angry and cheated and went to the Gestapo because he thought he could frame the testing facility. He was to deliver the people to the Gestapo and get three thousand guilders for his part. However, Henk was still trusted by the men of the resistance.

The De Graaff farm was the rendezvous point that night. The journey of the group in Henk’s truck from Rotterdam to Simonshaven went smoothly. They had no trouble crossing the bridge at Spijkenisse, as Henk had all the right papers (and as had been previously agreed with the Gestapo, unknown to his cargo). Pending darkness they all sat together at the De Graaff farm. The boat was ready in the port and the passengers were pleased, because everything had gone so well. Maarten de Graaff was out but Mrs de Graaff looked after them. Suddenly the alarm was sounded - Germans had surrounded them. Everyone tried to flee but all exits were blocked. They tried to hide – in the barn, in the hay, in the cupboards: Professor Fischer, a Czech, hid in a potato crate. He heard the heavy boots of the Germans and saw the bright light of a lantern through the cracks. He lay still, but the search of the house and barn took hours. Finally two cars drove away with their prisoners. Mrs de Graaff was also taken. But the Germans knew how many people had been in the vehicle and they were one short. He knew they would be back.

When he surfaced, he found De Graaff in the living room company of his neighbours. The neighbour did not dare accommodate him, but De Graaff told him to stay at his. He knew what he risked. The Germans did indeed come back and again Professor Fischer hid in the crate. He was lucky as they did not find him and lived to tell this tale but Maarten de Graaff was taken and imprisoned. He was sent with some others to Kamp Vught (KZ Herzogenbusch) in Amsterdam and then onto the concentration camp Natzweiler/Struthof (now Alsace, France, then annexed by Germany), where he died on April 4th 1944.

Mrs de Graaff was released six months later, a broken woman. She operated the ferry until her departure in 1954, which ended the long connection between Piershil and Putten. Professor Josef Ludvík Fischer (1894 - 1973) was appointed in 1947 as the first rector of the new Palacký University in Olomouc. The Special Court in Rotterdam convicted the driver Henk Luyendijk on the 22nd March 1946 for his betrayal. He got ten years in prison, of which he had to serve a little more than six years.

In 1971 Maarten de Graaff was posthumously awarded the Resistance Cross. In the late seventies he had a road named after him ‘M. de Graaffstraat’, on the edge of the village Simonshaven. A small gathering of family and several former Engelandvaarders, including sea captain lieutenant Mr HW Keesom, were at the unveiling of the street sign.

Maarten de Graaff knew what he was doing and was willing to risk his own life and even the wellbeing of his family to help others escape Nazi occupied Holland. He well deserved these posthumous tokens of appreciation.

Born in Rozenburg on the 8th December 1874, he lived on his father’s farm for nineteen years. In 1915, he moved with his wife to Simonshaven, where he worked as the operator of the pumping station and also ran the ferry service from Piershil on the Spui to the Biersum on Putten. There used to be small port with a jetty at Piershil. Pedestrians and cyclists could pull on a bell and the ferryman would take them in his rowboat to the Biersum on Putten (Putten translates as Wells).

When the Nazis invaded the Netherlands, Maarten de Graaff joined the resistance. He was 65 years old. He was part of a team who helped prepare crossings to England for Engelandvaarders. One of the ways in which he did this was by taking ‘passengers’ offshore in the dark in his speedboat where they were picked up by a British submarine. He would then wait until the tide turned and quietly return to shore in his boat.

On the 21st March 1942, another so-called resistance fighter Henk Luyendijk, a driver from Rotterdam, betrayed him. In December 1941 a plan was put together to take a number of people, mostly Jews but also some marines, to England. Henk was in on the plan from the beginning, which he revealed to the Gestapo. He also delivered petrol needed for crossings to the resistance. The quality of petrol was tested regularly and one day his ‘petrol’, whilst it smelt of petrol, was clearly not. When he was told, he felt angry and cheated and went to the Gestapo because he thought he could frame the testing facility. He was to deliver the people to the Gestapo and get three thousand guilders for his part. However, Henk was still trusted by the men of the resistance.

The De Graaff farm was the rendezvous point that night. The journey of the group in Henk’s truck from Rotterdam to Simonshaven went smoothly. They had no trouble crossing the bridge at Spijkenisse, as Henk had all the right papers (and as had been previously agreed with the Gestapo, unknown to his cargo). Pending darkness they all sat together at the De Graaff farm. The boat was ready in the port and the passengers were pleased, because everything had gone so well. Maarten de Graaff was out but Mrs de Graaff looked after them. Suddenly the alarm was sounded - Germans had surrounded them. Everyone tried to flee but all exits were blocked. They tried to hide – in the barn, in the hay, in the cupboards: Professor Fischer, a Czech, hid in a potato crate. He heard the heavy boots of the Germans and saw the bright light of a lantern through the cracks. He lay still, but the search of the house and barn took hours. Finally two cars drove away with their prisoners. Mrs de Graaff was also taken. But the Germans knew how many people had been in the vehicle and they were one short. He knew they would be back.

When he surfaced, he found De Graaff in the living room company of his neighbours. The neighbour did not dare accommodate him, but De Graaff told him to stay at his. He knew what he risked. The Germans did indeed come back and again Professor Fischer hid in the crate. He was lucky as they did not find him and lived to tell this tale but Maarten de Graaff was taken and imprisoned. He was sent with some others to Kamp Vught (KZ Herzogenbusch) in Amsterdam and then onto the concentration camp Natzweiler/Struthof (now Alsace, France, then annexed by Germany), where he died on April 4th 1944.

Mrs de Graaff was released six months later, a broken woman. She operated the ferry until her departure in 1954, which ended the long connection between Piershil and Putten. Professor Josef Ludvík Fischer (1894 - 1973) was appointed in 1947 as the first rector of the new Palacký University in Olomouc. The Special Court in Rotterdam convicted the driver Henk Luyendijk on the 22nd March 1946 for his betrayal. He got ten years in prison, of which he had to serve a little more than six years.

In 1971 Maarten de Graaff was posthumously awarded the Resistance Cross. In the late seventies he had a road named after him ‘M. de Graaffstraat’, on the edge of the village Simonshaven. A small gathering of family and several former Engelandvaarders, including sea captain lieutenant Mr HW Keesom, were at the unveiling of the street sign.

Maarten de Graaff knew what he was doing and was willing to risk his own life and even the wellbeing of his family to help others escape Nazi occupied Holland. He well deserved these posthumous tokens of appreciation.

Additional References

1. Amongst my papers

a. Lezing te houden op het Koninklijk Instituut voor de Marine te Eynshouse door... Beschrijving van de tocht per reddingboot vanuit Zeeland va 4 tot 4 april 1941. (Translation: Lecture at the Royal Institute for the Navy in Eynshouse by...Account of the journey by life-boat from Zeeland on the 3rd to 4th of April 1941). In two parts: 'Preparation' and 'Overall situation in Holland'). From amongst Keesom’s papers in Opa’s possession. Sent to Opa by Woltjer with a letter dated 1966. Kindly translated by Inge de Jong.

b. Letter to Keesom from De Niet, 1st July 1941. From amongst Keesom’s papers in Opa’s possession. Sent to Opa by Woltjer with a letter dated 1966. Kindly translated by Inge de Jong.

c. Second Meeting with the Prince (cutting from Dundee Courier, 1972 - no exact date but interview before Holyrood Palace meeting)

2. Dressing, AMF. Tulpen voor Wilhelmina. De geschiedenis van de Engelandvaarders. PhD thesis, FGW: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG), 2004. P97-98.

3. Katwijkers en Engelandvaart

Translation

3. Maarten de Graaff – een grote verzetsstrijder (a great freedom fighter)

Translation

4. 1942 – Het verraad van de pontbaas (The Betrayal of the Ferry Boss)

Translation

5. M. de Graaffstraat

Translation

6. Bronze Cross database entry

7. Other background information

Seyss-Inquart

Dutch Resistance

National Socialist Movement

Wilton Fijenoord

Dutch Government in exile

Plaque 9152

a. Lezing te houden op het Koninklijk Instituut voor de Marine te Eynshouse door... Beschrijving van de tocht per reddingboot vanuit Zeeland va 4 tot 4 april 1941. (Translation: Lecture at the Royal Institute for the Navy in Eynshouse by...Account of the journey by life-boat from Zeeland on the 3rd to 4th of April 1941). In two parts: 'Preparation' and 'Overall situation in Holland'). From amongst Keesom’s papers in Opa’s possession. Sent to Opa by Woltjer with a letter dated 1966. Kindly translated by Inge de Jong.

b. Letter to Keesom from De Niet, 1st July 1941. From amongst Keesom’s papers in Opa’s possession. Sent to Opa by Woltjer with a letter dated 1966. Kindly translated by Inge de Jong.

c. Second Meeting with the Prince (cutting from Dundee Courier, 1972 - no exact date but interview before Holyrood Palace meeting)

2. Dressing, AMF. Tulpen voor Wilhelmina. De geschiedenis van de Engelandvaarders. PhD thesis, FGW: Instituut voor Cultuur en Geschiedenis (ICG), 2004. P97-98.

3. Katwijkers en Engelandvaart

Translation

3. Maarten de Graaff – een grote verzetsstrijder (a great freedom fighter)

Translation

4. 1942 – Het verraad van de pontbaas (The Betrayal of the Ferry Boss)

Translation

5. M. de Graaffstraat

Translation

6. Bronze Cross database entry

7. Other background information

Seyss-Inquart

Dutch Resistance

National Socialist Movement

Wilton Fijenoord

Dutch Government in exile

Plaque 9152